Inside Financial Services

Vol. V, No. 16

TOM BROWN’S BANKING WEEKLY: 4/17/20

Financial Services Insights and Intelligence

FIRST WORD: Earnings observations. Normally, I don’t have much to say about banks’ quarterly earnings until after everyone has reported, but these aren’t normal times. Closing out the week, here are a few observations.

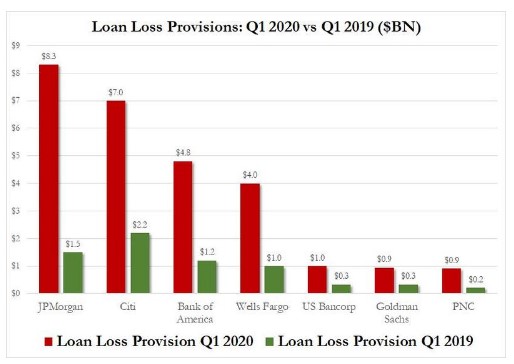

- Why was there such a violent price reaction to the reports? I don’t understand it, and think it can only be explained by fear and uncertainty. Bank stocks had already declined by 30% before earnings season started, on fears of higher credit losses and declining year-on-year earnings. Banks showed positive earnings despite massive reserve building—and the stocks dropped another 15%. I don’t get it. Loan loss reserves are just loss-absorbing capital moved to another place on the balance sheet.

- CECL adoption couldn’t have come at a worse time. Many of us were very vocal in our skepticism of the new CECL rules on loan loss reserving, as the rules will make bank earnings even more pro-cyclical than they already were. Well, it didn’t take long to be proven right. Let’s take JPMorgan as an example. At the end of 2019, the company’s loan loss reserve was $14.3 billion, and not a single analyst or investor questioned its adequacy. Then the company adopted CECL on January 1 and, because the new accounting standard requires banks to estimate, based on all sorts of economic factors, the expected loss of every loan over its expected life, JPMorgan’s loan loss reserve was increased by $4.3 billion or 30%. Obviously, the world hadn’t changed dramatically overnight, but our “friends” at FASB felt better. Then in March, the global economy stopped in its tracks, and JPMorgan had to estimate the lifetime losses in its loan portfolio using an entirely different set of economic assumptions, based on what it thinks will happen in an environment that no one has ever experienced. Based on its models, the company increased its loan loss reserve by $6.8 billion, or 37%. So when JPMorgan reported its period-end balance sheet, it had a loan loss reserve of $25.4 billion, or 78% higher than the $14.3 billion it had just 91 days earlier. Yet despite the massive reserve building, the company still reported positive net income of $3 billion.

- Analysts question whether the loan loss reserves are high enough. Every large bank that reported earnings this week was repeatedly grilled about the economic assumptions used in its forecasting model. Bank of America was the best at avoiding that tar baby, and simply kept saying it wasn’t going to give out individual line-item forecasts such as the assumed peak unemployment rate, because there were 50 or so variables in its model, and to compare one of Bank of America’s assumptions to another large bank’s to determine which company was more conservative could be terribly misleading. You could give analysts and investors all the economic assumptions used, and that still wouldn’t help them make any better judgements about the adequacy of the loan loss reserves.

- Reserves compared to CCAR worst-case stress losses. After Bank of America reported its first-quarter earnings, its investor relations department spent all day fielding questions on how the loan loss reserve was calculated. One analyst couldn’t understand why the bank’s loan loss reserve was only $17 billion, when its cumulative losses under the worst-case stress test assumptions were $44 billion. Trying to explain the different environments and different assumptions proved useless, so finally some shorthand worked. Assume the $44 billion of losses will occur, then that will require $27 billion more in reserve build. After-tax that would take just 100 basis points off the company’s CET1 capital calculation, moving it from 10.8% to 9.8%.

- The analysts appeared to want more certainty this week from the bank managements—in what’s a very uncertain environment.

My biggest takeaways from the earnings reports so far is how much better the large banks are positioned today than they used to be from a capital, liquidity, and risk-management perspective to deal with the actual credit problems that will develop. The other takeaway is that I would expect less reserve-building in the next two quarters, and then large reserve releases in 2021 as CECL turns out to be just who we thought it was.

JOHNNY ALLISON WISDOM: I’m not the only one frustrated by the adoption of CECL and the needless punishment it’s inflicting on bank earnings. Home Bancshares CEO Johnny Allison had this to say on the matter during his company’s earnings call yesterday:

Then in the midst of the pandemic, with thousands of people dying, and hundreds of thousands people infected, and Americans locked in their homes, the accounting clowns show up with the new circus act called CECL. Total disregard for the mess they’ve created by creating uncertainty in the market. The circus genie should have never been allowed to get out of the bottle.

No disrespect to accounting. The program was created by a bunch of accountants who probably have never run a business in their lives. They account for what others do. That’s why they call them accountants. Now they’re creating a new industry just to solidify their position forever in the space of banks, while creating for banks hundreds of millions of dollars of additional expenses to pay for the Barnum and Bailey act called CECL. The rational thing to do was to look at how banks maneuver through the worst economic cycle in 80 years and reserve properly.

Pretty simple, a 1.5% to 2% reserve has been sufficient for us while making specific allocation reserves rewarded. However, this doesn’t cost much and doesn’t create much distraction. Guess what, after all the costs, all the distraction, all the people, all the modeling and the reserve getting hit with an additional $71 million due to unemployment for the month, our reserve came out at 2.01%. You cannot make this stuff up.

Amen to that. The entire transcript is well worth reading, by the way.

LOOKING AHEAD: Optimism lives! Over the past 45 days, bookings on cruises in 2021 have risen by 40% compared to 2019, according to CruiseCompete.com.

NO HELP: The next few quarterly earnings-reporting seasons are going to be real adventures, I tell you. As of last Friday, 295 companies in the S&P 1500 had withdrawn their earnings guidance, up from six on March 6, according to the Wall Street Journal.

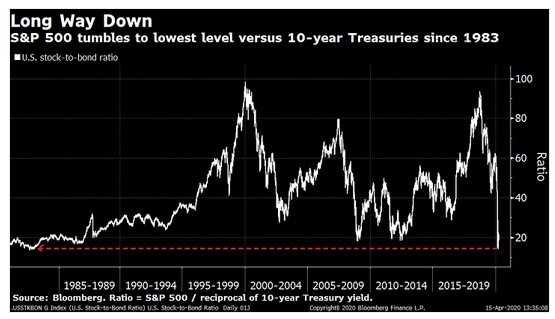

WAY DOWN: Here’s an extreme. The ratio of the S&P 500 to the reciprocal of the yield on the ten-year Treasury is now lower than it’s been since 1983—a time, you may recall, when the stock market was at the very beginning of an extended, historic run higher.

A STEADY HAND: I’d love to know who on the investment policy committee in Goldman Sachs’s research department—assuming Goldman research still has an investment policy committee—thought it was a good idea to let strategist David Kostin raise his price target for the S&P 500 on Monday by a whopping 50%, to 3000, after he’d cut it to 2000 just three weeks prior. How helpful! Purely from a PR and marketing standpoint, after all, the move reveals exactly the sort of flighty, weather-vane-ish investment judgement on Kostin’s part that sell-side research is supposed to (I thought) provide a nuanced counterbalance to. Not this time! It turns out that strategists can get as spooked as the rest of us. Necessary proviso: On the merits, Kostin’s move makes total sense. In his initial, target-chopping panic, he simply failed to realize that the federal government really would stop at nothing to prevent an economy-wide liquidity crunch.

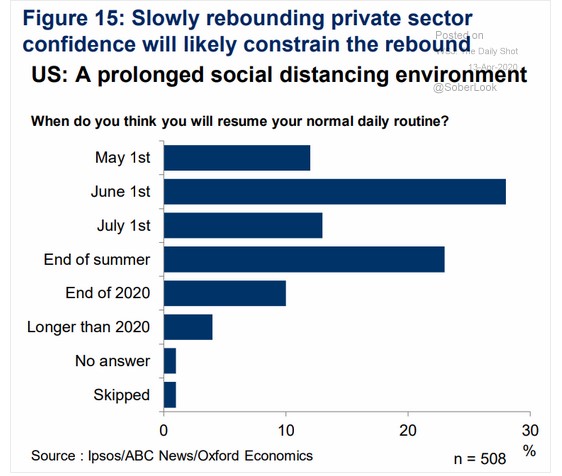

SOONER RATHER THAN LATER: I’m not sure this is the schedule a lot of the medical poobahs I’m hearing have in mind. More than 50% of Americans say they expect to get back to their regular routines by July 1.

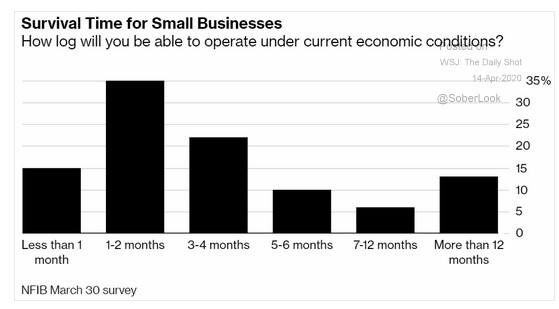

BACK TO WORK: Here’s one big reason, by the way, why people are so ready to resume a normal life. Roughly half of small-business owners surveyed by the National Federation of Independent Business say their business can operate under a lockdown for only two months or less.

LESS IS MORE: Say, maybe the country’s new habit of working at home really will cause a permanent dent in demand for certain types of commercial real estate. Bloomberg, yesterday:

James Gorman is hesitant to make predictions about the future with so much about the coronavirus pandemic still uncertain. One thing is clear, however: Morgan Stanley will have “much less real estate.”

“We’ve proven we can operate with no footprint,” Gorman, the firm’s chief executive officer, said in an interview Thursday with Bloomberg Television. “Can I see a future where part of every week, certainly part of every month, a lot of our employees will be at home? Absolutely.” [Emphasis added.]

Ninety percent of Morgan Stanley’s employees are lately working from home, Bloomberg says, so that, if the firm really puts its mind to it, it really could shed a serious amount of square footage.

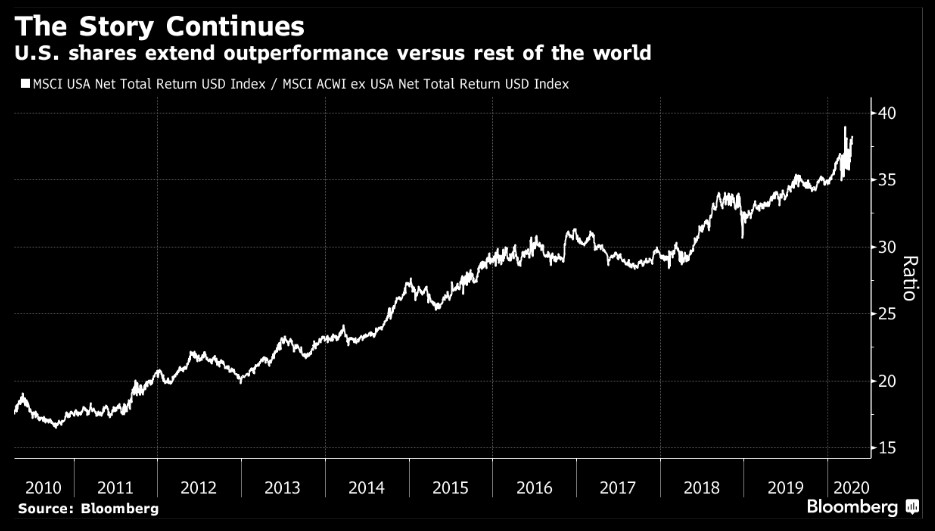

EVERYTHING’S RELATIVE: And here you’ve been thinking owning U.S. stocks has been painful lately. From Bloomberg, yesterday: “U.S. Stocks on Brink of Record Versus World While Virus Rages.”

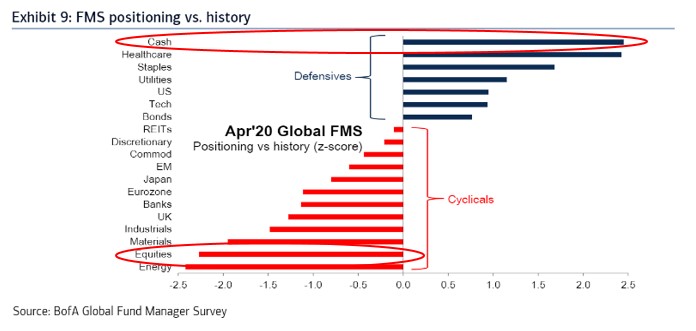

SHELTERING IN PLACE: Such boldness in the face of uncertainty! With stock prices still 20% off their highs, portfolio managers surveyed by Bank of America say they are overweight cash, on average, relative to the past, and underweight equities.

What the heck ever happened to “Be greedy when others are fearful”?

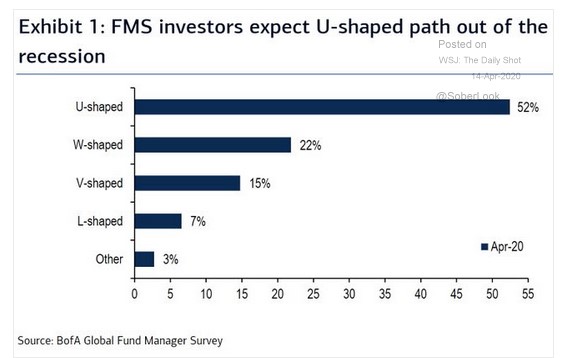

TOO JADED: Along that same line, just 15% of those same managers expect a V-shaped recovery:

Seriously? I understand that the default attitude of the typical Wall Street type is supposed to be a sort of world-weary pessimism, but this is a bit much, wouldn’t you say? Unlike during most slowdowns, after all, the underlying structure of the economy now is still in pretty good shape. The financial system doesn’t need to be fixed, for example, as it did following the last slowdown. There are no mountains of unsold inventories to liquidate. And given programs like the PPP, consumers’ finances are still pretty strong. So once the lock-down ends (which increasingly looks like will happen sooner rather than later), there isn’t much to prevent the economy from picking up steam pretty fast.

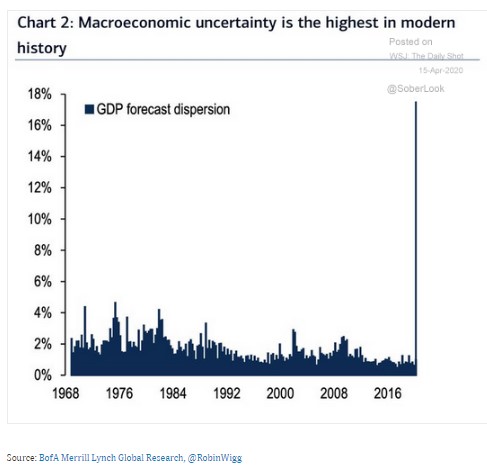

INTO THE UNKNOWN: Here’s why you should be even more skeptical than usual of the macroeconomic forecasts being put out by economists. Those forecasts have never been so all-over-the-place:

Basically, nobody knows anything.

BLIND: Speaking of no one knowing anything, one unremarked-upon aspect of the current economic and market situation—at least, unremarked-upon by anyone I’ve heard—is that, for once, things really are different this time. An epidemic of this apparent severity has basically not happened in anyone’s lifetime, and the last time an epidemic this bad did occur, in 1918, there were no antibiotics or antivirals available to mitigate it. So it’s all totally new—which means that looking at history to see how events might play out probably won’t be too helpful. I happen to think things will improve well before the consensus seems to (see above), but what do I really know? Again, nobody knows anything.

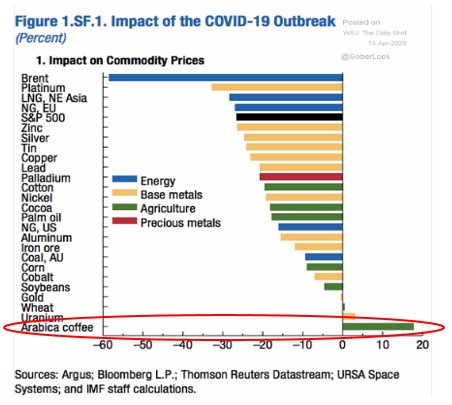

PERKED UP: Don’t ask me why, but basically the only commodity that’s actually had a meaningful rally since the start of the outbreak is . . . Arabica coffee.

UNBALANCED: It is as inevitable as the tides. The very same industry analysts who are pointing to the big loan loss reserves the big banks took last quarter as a reason to be negative on the group will, once the recession is over, dismiss those same banks’ sudden and inevitable earnings recoveries as unimpressive because, the analysts will say, the gains are merely reserve reversals.

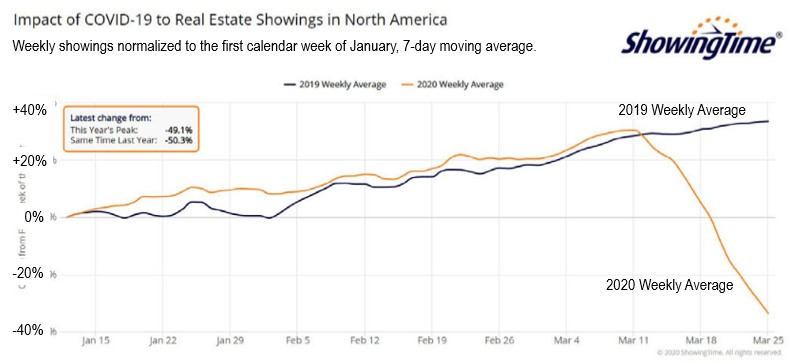

NOT SHOWING UP: Here’s another business that’s essentially ground to a halt as a result of the coronavirus lockdown: residential real estate brokerage.

LOOSE CANNON: Hang on a minute. Minneapolis Fed President Neil Kashkari says that his bank’s work shows that, in anticipation of a stressed environment, the large banks should suspend their dividends and raise $200 billion in equity capital? But the Fed is the one that runs the actual stress tests that are applied to the banks every year! If Kashkari doesn’t believe the Fed’s current stress-testing regimen is adequate, he should take the matter up with his Fed colleagues, rather than simply barking for more capital.

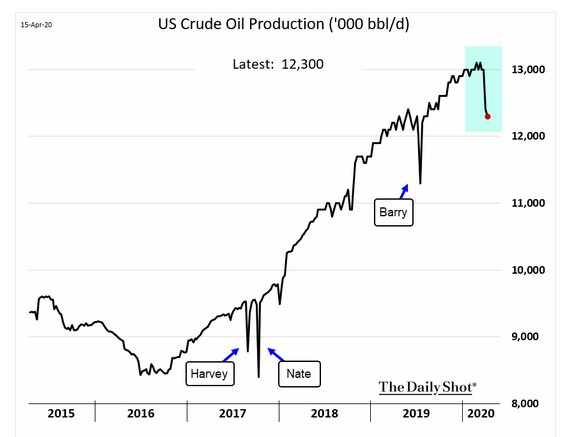

FALLING: Well, finally. The collapse in global energy demand has at last led to decline in domestic crude-oil production. It used to take a hurricane in the Gulf to do that.

HOW CONVENIENT: Goldman Sachs only marked down its private equity portfolio by 3% in the first quarter? Really? Call me crazy, but I have a feeling that investor interest in PE is about to surge even higher.

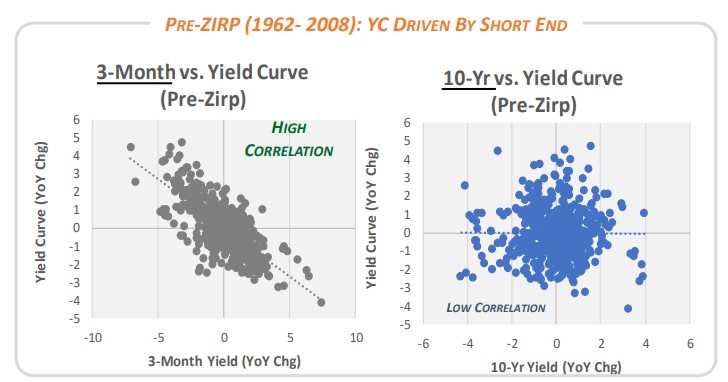

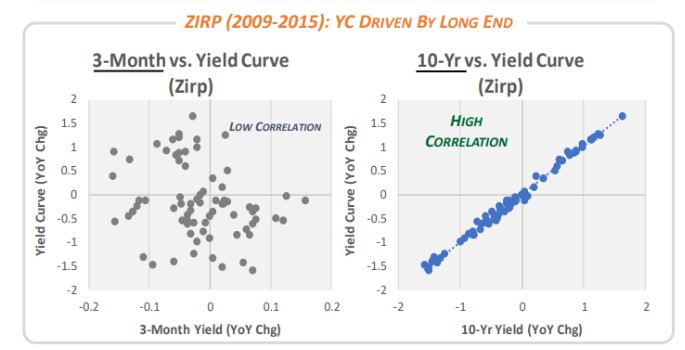

LEADING INDICATOR BECOMES COINCIDENT INDICATOR: Fed policy doesn’t drive the shape of the yield curve the way it once did. Cornerstone Macro pointed out this week that, prior to the era of the Fed’s zero-interest rate regime that began in 2008, changes at the short end of the curve, which were largely controlled by the Fed, were a good leading indicator of interest rates. No longer. In the current ZIRP environment, the yield curve is now driven by changes in the long end.

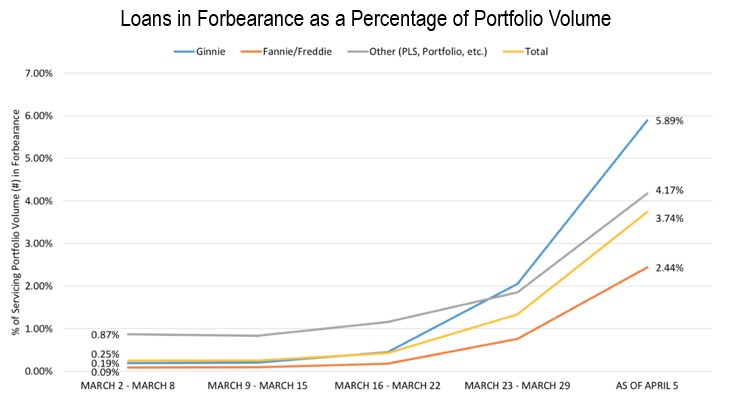

UNDERSTANDABLE INCREASE: The Mortgage Bankers Association reports that the percentage of mortgage loans in forbearance rose to 2.66% at the beginning of April from 0.25% at the beginning of March. Any reasonable person would expect that number to keep moving higher until people can go back to work.

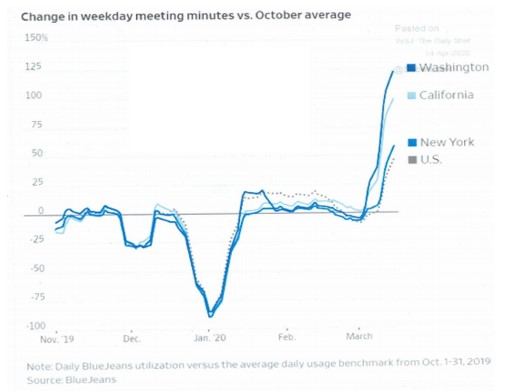

WE NEED TO TALK: No surprise here. The amount of time people are spending on videoconferences is surging.

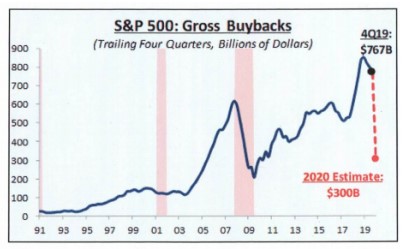

FEWER BUYBACKS: The biggest net buyers of equities over the past few years have been (by far) companies buying back their own stock. With the virus outbreak, though, that’s changing. Something like $200 billion of buyback programs have been suspended in recent weeks. Wolfe Research estimates the suspensions will reach $500 billion by later this year.

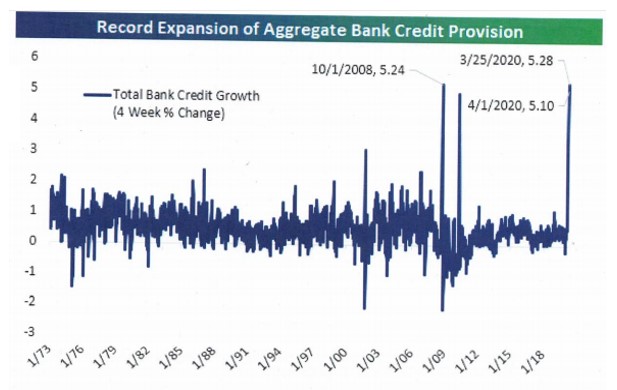

VISUALIZING THE LOAN GROWTH: Bank borrowers suddenly all want to add liquidity at once. Over the final four weeks of March, the banking industry as a whole saw a 5.1% jump in total loans and a 20.6% increase in commercial loans, in particular, in large part as companies drew down their credit lines. The pace has apparently slowed sharply so far in April.

POSTAL SERVICE BLEEDING: In large part because of a 30% reduction in mail volume since the start of the virus outbreak, expected operating losses at the Postal Service have ballooned by so much that the USPS is telling Congress that absent an emergency loan, it will be “financially illiquid” by the end of September. Last week, Postmaster General Megan Brennan, apparently believing you either go big or go home, asked Congress for $75 billion in cash, grants, and loans.

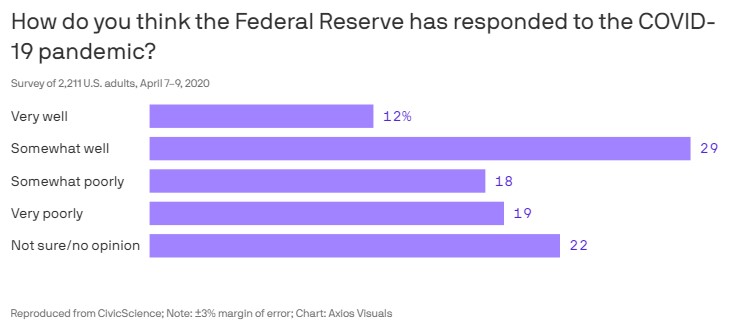

EVALUATING THE FED: Some people are just hard to please. Fully 37% of Americans surveyed by CivicScience say they think the Fed is handling the coronavirus outbreak either somewhat poorly or very poorly. I mean, what more do these folks think the Fed should be doing?

KETTLEBELL SHORTAGE: It’s one crisis after another. The sole domestic manufacturer of kettlebells, items that are suddenly in high demand as gyms have closed and more people are working out at home, can only turn out 40 to 50 per day. In the meantime, 65% of global kettlebell production comes from (surprise!) China, which halted production in January.

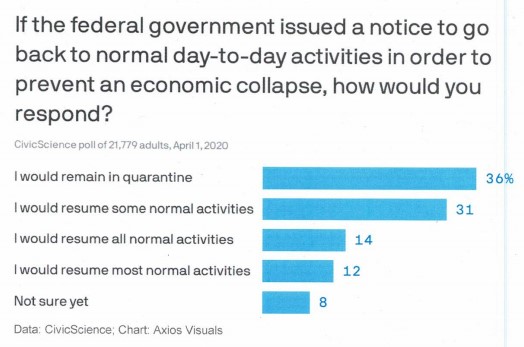

GOING BACK TO WORK: Americans seem to be warming up to the idea of getting out and about again. Only 36% of people polled say they’d stay in quarantine even after the lockdown ends, down from 42% who said so last month.

LESSONS FROM PRIOR EARNINGS REPORTING SEASONS: To mark the start of his 100th earnings season, last week Barclays bank analyst Jason Goldberg (one of the few good ones on the sell side) wrote a piece sharing twelve observations he has about earnings seasons. These were my four favorites.

- “Bank investors tend to obsess over a metric (or two) each quarter, and it varies quarter to quarter and sometimes even intra-quarter.” What Goldberg doesn’t say, but what I believe, is that usually managements can predict what metric will be focused on, and will be prepared to talk about it in some detail, but they shouldn’t let their call be hijacked by a myopic focus on a single number.

- “Very detailed disclosure doesn’t mean everything is OK; In fact, sometimes the opposite is true.” Reminds me of the phrase, “You doth protest too much.”

- “Be mindful of excessive one-timers.” Too often, some management teams want to exclude all the negative items when calculating what they want to think of as operating earnings.

- “Analysts typically under-forecast loan loss provisions when credit conditions are getting worse, and overestimate them when things are improving/stable.” This will be particularly true this year in light of the unprecedented decline in economic activity and the adoption of CECL.

Since I have more earnings season experience (this is my 160th), than even Goldberg does, I have a few of my own additional observations.

- Too many managements spend way too much time reading numbers contained in the press release! Everyone can read the dollar amount of net income and what percent it changed from the prior years. Please stop and tighten up the calls.

- If you feel compelled to go into details about large problem loans, don’t, since usually you’re being too optimistic about the odds of the loans’ positive resolution.

- Don’t let the change in the stock’s price on the day of the release change your long-term view of the value of your company.

- For entertainment purposes, listen to the JPMorgan earnings conference call and wait for Wells Fargo analyst Mike Mayo to ask a question directed solely to Jamie Dimon. At Second Curve we we’ve turned it into a betting game.

NEXT WEEK: A couple of purchasing manager indices out next week will bear watching. On Thursday, Markit will release its April PMIs for Manufacturing and Services. For manufacturing, the consensus expectation is 38.5 vs 48.5 in March; for services, the consensus looks for 39.0 vs 39.8.

THE LAST WORD: With no gym to go to, Amy and I have resorted to evening walks around the neighborhood, sometimes with one or more of our kids joining us. I have two significant takeaways from this new habit. First, the people out walking now are more friendly then they used to be. When Amy and I walked before Covid-19, no one would say hello unless I said it first. Now, people are as likely to say hello first to us as we are to them. Second, Amy needs a better vocal filter, both for content and volume. For example, when we walked by one neighbor’s house, she announced that “I hate those fake flowers,” not realizing the neighbor across the street was standing right there. Then as we passed another neighbor’s house, with their kids playing in the yard, a loud f-bomb came out of her mouth. But my favorite was when a neighbor driving her car full of kids and dog stopped to talk and Amy asked, “is that family living across the street from you gone yet?’ At which point the neighbor introduced us to the kids of that family. The parents, it turns out, are divorcing and moving. The gym’s re-opening can’t come fast enough for me.

Edited by Matt Stichnoth.

Copyright © 2020, Second Curve Capital LLC

Copyright notice: This publication is protected by copyright. It is a violation of federal law to reproduce or forward all or part of it to anyone. This includes photocopying, faxing, e-mail forwarding, and Web site posting. The Copyright Act imposes liability of up to $150,000 per issue for infringement.